All the Khan’s Horses

With fresh mounts in reserve, Genghis Khan’s

warriors could outlast any enemy.

In August 1227, a somber funeral procession—escorted the body of perhaps the most renowned conqueror in world history-made its way toward the Burkhan Khaldun (Buddha Cliff) in northeastern Mongolia

|

| mongol empire |

Commanding a military force that never amounted to

more than 200,000 troops, this Mongol ruler had united the disparate, nomadic

Mongol tribes and initiated the conquest of territory stretching from Korea

to Hungary

and from Russia

to modern Vietnam

and Syria.

His

title was Genghis Khan, “Khan of All Between the Oceans.”

Genghis Khan and his descendants could not have

conquered and ruled the largest land empire in world history without their

diminutive but extremely hardy steeds.

|

| mongolian ponies1_Deborah Kalin |

In

some respects, these Mongolian ponies resembled what is now known as

Przewalski’s horse. Mongols held these horses in highest regard and accorded

them great spiritual significance.

|

| mongolian ponies2_Deborah Kalin |

Before setting forth on military

expeditions, for example, commanders would scatter mare’s milk on the earth to

insure victory. In shamanic rituals, horses were sacrificed to provide

“transport” to heaven.

|

| Mongol Cavalrymen |

The Mongols prized their horses

primarily for the advantages they offered in warfare.

In combat, the horses

were fast and flexible, and Genghis Khan was the first leader to capitalize

fully on these strengths.

After hit-and-run raids, for example, his horsemen

could race back and quickly disappear into their native steppes.

|

| Mounted Archers |

Enemy armies from the sedentary

agricultural societies to the south frequently had to abandon their pursuit

because they were not accustomed to long rides on horseback and thus could not

move as quickly. Nor could these farmer-soldiers leave their fields for

extended periods to chase after the Mongols.

| Mongol_soldiers_mongol bow__by_Rashid_al-Din_1305 |

The Mongols had developed a composite bow made out of sinew and

horn and were skilled at shooting it while riding, which gave them the upper

hand against ordinary foot soldiers.

|

| composite bow |

With a range of more than 350 yards, the

bow was superior to the contemporaneous English longbow, whose range was only

250 yards.

| MONGOLIAN BOW 1-1 |

|

| Mongol light horse archer.Equipped with a deadly composite bow and armour piercing arrows |

|

| Mongol light horse archer |

A

wood-and-leather saddle, which was rubbed with sheep’s fat to prevent cracking

and shrinkage, allowed the horses to bear the weight of their riders for long

periods and also permitted the riders to retain a firm seat.

|

| Mongol Heavy cavalry.Well equipped with steel lamellar armour his main weapons were the lance[not shown],sabre and mace |

Their saddlebags

contained cooking pots, dried meat, yogurt, water bottles, and other essentials

for lengthy expeditions. Finally, a sturdy stirrup enabled horsemen to be

steadier and thus more accurate in shooting when mounted.

|

| Ilkhanid Horse Archer |

A

Chinese chronicler recognized the horse’s value to the Mongols, observing that

“by nature they [the Mongols] are good at riding and shooting.

Therefore they

took possession of the world through this advantage of bow and horse.”

|

| Mongol Archer |

Genghis Khan understood the importance

of horses and insisted that his troops be solicitous of their steeds. A cavalryman

normally had three or four, so that each was, at one time or another, given a

respite from bearing the weight of the rider during a lengthy journey.

|

| A mongol Elite cavalryman or commander.Magnificently equipped in steel lamellar armour. |

Before

combat, leather coverings were placed on the head of each horse and its body

was covered with armor. After combat, Mongol horses could traverse the most

rugged terrain and survive on little fodder.

|

| il-Khan Hulagu rests |

According to Marco Polo,

the horse also provided sustenance to its rider on long trips during which all

the food had been consumed.

On such occasions, the rider would cut the horse’s

veins and drink the blood that spurted forth.

Marco Polo reported, perhaps with

some exaggeration, that a horseman could, by nourishing himself on his horse’s

blood, “ride quite ten days’ marches without eating any cooked food and without

lighting a fire.”

And because its milk offered additional sustenance during

extended military campaigns, a cavalryman usually preferred a mare as a mount.

The milk was often fermented to produce kumiss, or araq, a potent alcoholic

drink liberally consumed by the Mongols. In short, as one commander stated, “If

the horse dies, I die; if it lives, I survive.”

Mongol

Military Tactics and Exploration

Mobility and surprise characterized the

military expeditions led by Genghis Khan and his commanders, and the horse was

crucial for such tactics and strategy.

Horses could, without

exaggeration, be referred to as the intercontinental ballistic missiles of the

thirteenth century.

|

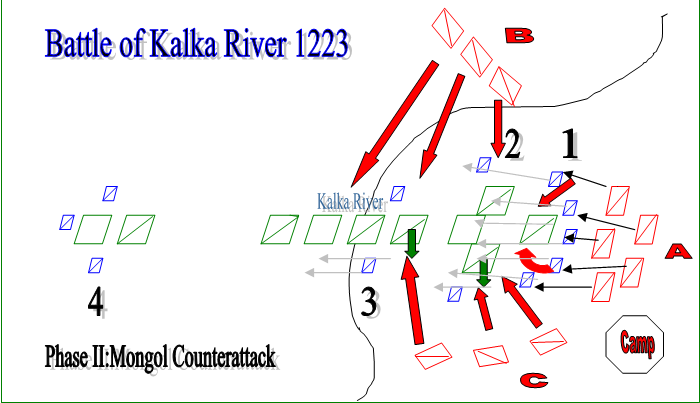

| The Mongols at the battle of the Kalka. |

The battle of the Kalka River, now renamed the Kalmyus

River, in southern Russia is a good example of the kind of campaign Genghis

Khan waged to gain territory and of the key role of horses.

|

| The Battle of Kalka River 1223 AD |

After his relatively easy

conquest of Central Asia from 1219 to 1220, Genghis Khan had dispatched about

30,000 troops led by Jebe and Subedei, two of his ablest commanders, to conduct

an exploratory foray to the west. After several skirmishes in Persia, the

advance forces reached southern Russia.

|

| PHASE 1 Russian Advance |

In an initial engagement, the Mongols,

appearing to retreat, lured a much larger detachment of Georgian cavalry on a

chase. When the Mongols sensed that the Georgian horses were exhausted, they

headed to where they kept reserve horses, quickly switched to them, and charged

at the bedraggled, spread-out Georgians. Archers, who had been hiding with the

reserve horses, backed up the cavalry—with a barrage of arrows as they routed

the Georgians.

Continuing their exploration, the

Mongol detachment crossed the Caucasus Mountains, a daunting expedition during

which many men and horses perished. They wound up just north of the Black Sea

on the southern Russian steppes, which offered rich pasture lands for their

horses.

|

| PHASE 2 Mongol Counterattack. |

After a brief respite, they first

attacked Astrakhan to the east and then raided sites along the Dniester and

Dnieper Rivers, inciting Russian retaliation in May of 1223 under Mstislav the

Daring, who had a force of 80,000 men. Jebe and Subedei commanded no more than

20,000 troops and were outnumbered by a ratio of four to one.

Knowing that an

immediate, direct clash could be disastrous, the Mongols again used their

tactic of feigned withdrawal. They retreated for more than a week, because they

wanted to be certain that the opposing army continued to pursue them but was

spaced out over a considerable distance.

|

| PHASE 3 Allied Collapse |

At the Kalka River, the Mongols finally took a stand, swerving

around and positioning themselves in battle formation, with archers mounted on

horses in the front.

The Mongols’ retreat seems to have

lulled the Russians into believing that the invaders from the East were in

disarray. Without waiting for the remainder of his army to catch up and without

devising a unified attack, Mstislav the Daring ordered the advance troops to

charge immediately.

This decision proved to be calamitous. Mongol archers on

their welltrained steeds crisscrossed the Russian route of attack, shooting

their arrows with great precision. The Russian line of troops was disrupted,

and the soldiers scattered.

After their attack, the archers turned

the battlefield over to the Mongol heavy cavalry, which pummeled the already

battered, disunited, and scattered Russians.

Wearing an iron helmet, a

shirt of raw silk, a coat of mail, and a cuirass, each Mongol in the heavy

cavalry carried with him two bows, a dagger, a battleax, a twelve-foot lance,

and a lasso as his principal weapons. Using lances, the detachment of heavy

cavalry rapidly attacked and overwhelmed the Russian vanguard, which had been

cut off from the rest of their forces in the very beginning of the battle.

Rejoined by the mounted

archers, the combined Mongol force mowed down the straggling remnants of the

Russian forces. Without an escape route, most were killed, and the rest,

including Mstislav the Daring, were captured.

Rather than shed the blood

of rival princes—one of Genghis Khan’s commands—Jebe and Subedei ordered the

unfortunate commander and two other princes stretched out under boards and

slowly suffocated as Mongols stood or sat upon the boards during the victory

banquet.

The battle at the Kalka River

resembled, with some slight deviations, the general plan of most of Genghis

Khan’s campaigns.

|

| Statue of Ghengis Khan in Sükhbaatar Square FullMogul-wiikimedia-commons |

In less than two decades, Genghis Khan had, with the support

of powerful cavalry, laid the foundations for an empire that was to control and

govern much of Asia in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

He died on a campaign in Central Asia,

and his underlings decided to return his corpse to his native land. Any

unfortunate individual who happened to encounter the funeral cortege was

immediately killed because the Mongols wished to conceal the precise location

of the burial site.

At least forty horses were reputedly

sacrificed at Genghis Khan’s tomb; his trusted steeds would be as important to

him in the afterlife as they had been during his lifetime.

|

| genghis khan Chinggis Khaan statue horse equestrian mongolia 12 |

|

| Genghis Khan Equestrian Statue, Tsonjin Boldog, Mongolia |

RELATED REFERENCE:

*original post date Dec 2008

Sources:

Morris Rossabi

lacma.org/khan

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genghis_Khan

nhmag.com/master

defence.pk

commons.wikimedia.org

deborahkalin.com

flickr

lacma.org/khan

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genghis_Khan

nhmag.com/master

defence.pk

commons.wikimedia.org

deborahkalin.com

flickr

.jpg)

magnificient cruelty

ReplyDeleteIndeed...

ReplyDeleteEmpire straddled half the world

driven by vicious ambition, greed,

and a love for his horses:

e.g. his conquest of China

for the simple reason

just to look for greener

grass pasteurs

for his horses.