All the Khan’s Horses

All the Khan’s Horses

With fresh mounts in reserve, Genghis Khan’s

warriors could outlast any enemy.

In August 1227, a somber funeral procession—escorted the body of perhaps the most renowned conqueror in world history-made its way toward the Burkhan Khaldun (Buddha Cliff) in northeastern Mongolia.

|

| mongol empire |

Commanding a military force that never amounted to

more than 200,000 troops, this Mongol ruler had united the disparate, nomadic

Mongol tribes and initiated the conquest of territory stretching from Korea

to Hungary

and from Russia

to modern Vietnam

and Syria.

His

title was Genghis Khan, “Khan of All Between the Oceans.”

.jpg) |

| Genghis_Khan_The_Exhibition_(5465078899) |

Genghis Khan and his descendants could not have

conquered and ruled the largest land empire in world history without their

diminutive but extremely hardy steeds.

|

| mongolian ponies1_Deborah Kalin |

In

some respects, these Mongolian ponies resembled what is now known as

Przewalski’s horse. Mongols held these horses in highest regard and accorded

them great spiritual significance.

|

| mongolian ponies2_Deborah Kalin |

Before setting forth on military

expeditions, for example, commanders would scatter mare’s milk on the earth to

insure victory. In shamanic rituals, horses were sacrificed to provide

“transport” to heaven.

|

| Mongol Cavalrymen |

The Mongols prized their horses

primarily for the advantages they offered in warfare.

In combat, the horses

were fast and flexible, and Genghis Khan was the first leader to capitalize

fully on these strengths.

After hit-and-run raids, for example, his horsemen

could race back and quickly disappear into their native steppes.

|

| Mounted Archers |

Enemy armies from the sedentary

agricultural societies to the south frequently had to abandon their pursuit

because they were not accustomed to long rides on horseback and thus could not

move as quickly. Nor could these farmer-soldiers leave their fields for

extended periods to chase after the Mongols.

|

| Mongol_soldiers_mongol bow__by_Rashid_al-Din_1305 |

The Mongols had developed a composite bow made out of sinew and

horn and were skilled at shooting it while riding, which gave them the upper

hand against ordinary foot soldiers.

|

| composite bow |

With a range of more than 350 yards, the

bow was superior to the contemporaneous English longbow, whose range was only

250 yards.

|

| MONGOLIAN BOW 1-1 |

|

| Mongol light horse archer.Equipped with a deadly composite bow and armour piercing arrows |

|

| Mongol light horse archer |

A

wood-and-leather saddle, which was rubbed with sheep’s fat to prevent cracking

and shrinkage, allowed the horses to bear the weight of their riders for long

periods and also permitted the riders to retain a firm seat.

|

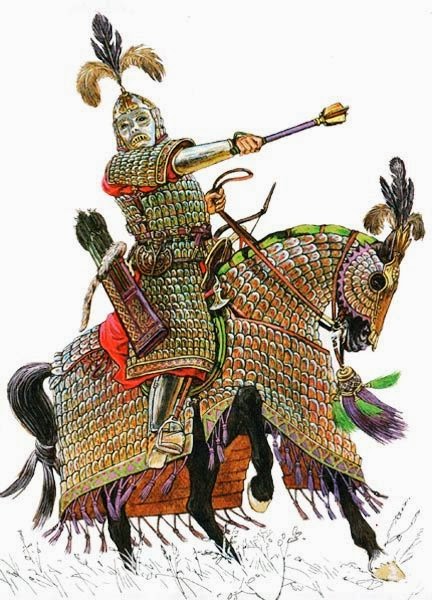

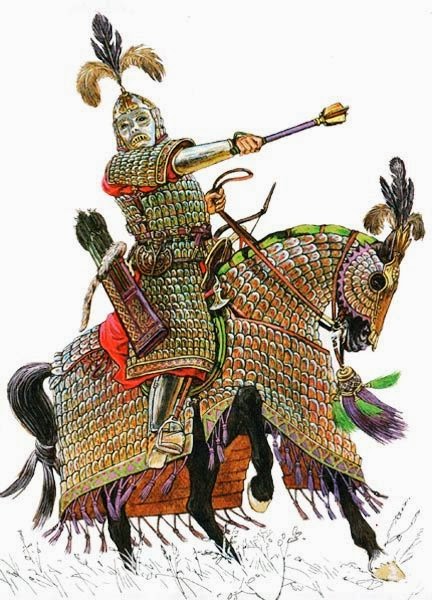

| Mongol Heavy cavalry.Well equipped with steel lamellar armour his main weapons were the lance[not shown],sabre and mace |

Their saddlebags

contained cooking pots, dried meat, yogurt, water bottles, and other essentials

for lengthy expeditions. Finally, a sturdy stirrup enabled horsemen to be

steadier and thus more accurate in shooting when mounted.

|

| Ilkhanid Horse Archer |

A

Chinese chronicler recognized the horse’s value to the Mongols, observing that

“by nature they [the Mongols] are good at riding and shooting.

Therefore they

took possession of the world through this advantage of bow and horse.”

|

| Mongol Archer |

Genghis Khan understood the importance

of horses and insisted that his troops be solicitous of their steeds. A cavalryman

normally had three or four, so that each was, at one time or another, given a

respite from bearing the weight of the rider during a lengthy journey.

|

| A mongol Elite cavalryman or commander.Magnificently equipped in steel lamellar armour. |

Before

combat, leather coverings were placed on the head of each horse and its body

was covered with armor. After combat, Mongol horses could traverse the most

rugged terrain and survive on little fodder.

|

| il-Khan Hulagu rests |

According to Marco Polo,

the horse also provided sustenance to its rider on long trips during which all

the food had been consumed.

On such occasions, the rider would cut the horse’s

veins and drink the blood that spurted forth.

Marco Polo reported, perhaps with

some exaggeration, that a horseman could, by nourishing himself on his horse’s

blood, “ride quite ten days’ marches without eating any cooked food and without

lighting a fire.”

And because its milk offered additional sustenance during

extended military campaigns, a cavalryman usually preferred a mare as a mount.

The milk was often fermented to produce kumiss, or araq, a potent alcoholic

drink liberally consumed by the Mongols. In short, as one commander stated, “If

the horse dies, I die; if it lives, I survive.”

.jpg)