That Classic White Sculpture Once Had Color

L - Augustus of Prima Porta is a 2.04m high marble statue of Augustus Caesar

"The aesthetic ideal of the Greeks was mimesis: the imitation of life. And it was color that brought their statues to life."

The art of the ancient Greeks and Romans is called classical art. This name is used also to describe later periods in which artists looked for their inspiration to this ancient style. The Romans learned sculpture and painting largely from the Greeks and helped to transmit Greek art to later ages. Classical art owes its lasting influence to its simplicity and reasonableness, its humanity, and its sheer beauty.

The first and greatest period of classical art began in Greece

They had learned to represent the human form naturally and easily, in action or at rest. They were interested chiefly in portraying gods, however. They thought of their gods as people, but grander and more beautiful than any human being.

They tried, therefore, to portray ideal beauty rather than any particular person. Their best sculptures achieved almost godlike perfection in their calm, ordered beauty.

The Greeks had plenty of beautiful marble and used it freely for temples as well as for their sculpture. They were not satisfied with its cold whiteness, however, and painted both their statues and their buildings.

Some statues have been found with their bright colors still preserved, but most of them lost their paint through weathering.

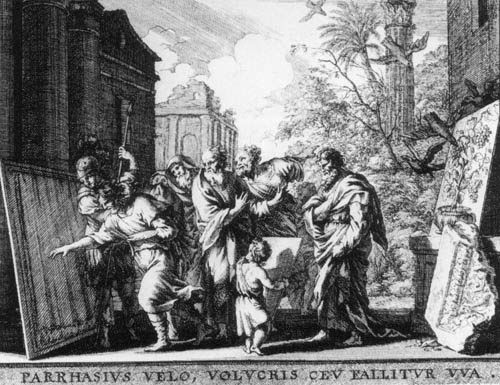

The works of the great Greek painters have disappeared completely, and we know only what ancient writers tell us about them.

Parrhasius, Zeuxis, and Apelles, the great painters of the 4th century BC, were famous as colorists. Polygnotus, in the 5th century, was renowned as a draftsman.

Fortunately we have many examples of Greek vases. Some were preserved in tombs; others were uncovered by archaeologists in other sites.

They are examples of the wonderful feeling for form and line that made the Greeks supreme in the field of sculpture.

By the 8th century BC the Greeks had become a seafaring people and began to visit other lands. In

For artists of the Renaissance, the key to truth and beauty lay in the past. Renaissance artists assiduously studied the sculptures and monuments of Greece and Rome

If those 15th and 16th century artists had looked more closely, however, they might have found something that would have changed their vision of ancient art and had a profound effect on their own practice. That element was COLOR. We now know that the unblemished white surface of Michelangelo’s “David”

or Bernini’s “St. Teresa in Ecstasy” would have been considered unfinished according to classical standards.

The sculpture and architecture of the ancient world was, in fact, brightly and elaborately painted. The only reason it appears white to us is that centuries of weathering have worn off most of the paint.

So entrenched has the association become between classical art and the look of white, unblemished marble, that the idea of an Athenian acropolis as colorfully painted as a circus wagon is difficult to imagine if not downright blasphemous.

But now an exhibition at the

Colored statues? To us, classical antiquity means white marble. Not so to the Greeks, who thought of their gods in living color and portrayed them that way too.

The temples that housed them were in color, also, like mighty stage sets. Time and weather have stripped most of the hues away.

And for centuries people who should have known better pretended that color scarcely mattered. White marble has been the norm ever since the Renaissance, when classical antiquities first began to emerge from the earth.

Remnants of the

Knowing no better, artists in the 16th century took the bare stone at face value. Michelangelo and others emulated what they believed to be the ancient aesthetic, leaving the stone of most of their statues its natural color.

Thus they helped pave the way for neo-Classicism, the lily-white style that to this day remains our paradigm for Greek art.

By the early 19th century, the systematic excavation of ancient Greek and Roman sites was bringing forth great numbers of statues, and there were scholars on hand to document the scattered traces of their multicolored surfaces.

Some of these traces are still visible to the naked eye even today, though much of the remaining color faded, or disappeared entirely, once the statues were again exposed to light and air. Some of the pigment was scrubbed off by restorers whose acts, while well intentioned, were tantamount to vandalism.

In the 18th century, the pioneering archaeologist and art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann chose to view the bare stone figures as pure—if you will, Platonic—forms, all the loftier for their austerity. "The whiter the body is, the more beautiful it is as well," he wrote.

"Color contributes to beauty, but it is not beauty. Color should have a minor part in the consideration of beauty, because it is not [color] but structure that constitutes its essence."

Against growing evidence to the contrary, Winckelmann's view prevailed. For centuries to come, antiquarians who envisioned the statues in color were dismissed as eccentrics, and such challenges as they mounted went ignored.

No longer; German archaeologist Vinzenz Brinkmann is on a mission.

Armed with high-intensity lamps, ultraviolet light, cameras, plaster casts and jars of costly powdered minerals, he has spent the past quarter century trying to revive the peacock glory that was Greece.

He has dramatized his scholarly findings by creating full-scale plaster or marble copies hand-painted in the same mineral and organic pigments used by the ancients: green from malachite, blue from azurite, yellow and ocher from arsenic compounds, red from cinnabar, black from burned bone and vine.

The ancients valued marble, Mr. Brinkmann says, but not

as we do. "In modern times," he explains, "marble has been

prized for its surface effect. Sculptors in antiquity knew it as the material

that would allow them to do exactly what they wanted. They thought about it as

filmmakers today think about their cameras. You got what you paid for. You

ordered a block of Parian marble -- the best there is -- and you paid a

fortune.

But once it was delivered, you could relax. Because in those 12 cubic

meters there would never be a fault or a flaw. If the sculptor wanted to make a

fold a meter long, he could do it. In limestone, he'd run into a shell or a

bump or a hole. The crystal structure of marble is absolutely pure and even.

It's the most homogeneous natural material in the world. It's a gift from God.

It's perfection." Once the sculptor had finished, however, it was the

painter's turn.

Nor was that the end of the story. "We think of

white marble figures as aesthetic monuments," Mr. Brinkmann says. "We

think of them as static, frozen in a museum installation. But we've learned by

our studies of polychromy that the interplay with architecture and the large

ornaments on the pediment of large structures in fact turned them into actors

on a kind of stage. And the more color they had, the more lifelike they

looked." Much in the manner of the builders of medieval cathedrals, the

Greeks told their great legends in pictures.

To illustrate how a marble Aphrodite might have appeared to the ancients, we asked German archaeologist Vinzenz Brinkmann, who has pioneered techniques of color restoration, to create a photomechanical reconstruction—never before published—of the first-century A.D. Roman Lovatelli Venus. It was excavated from the ruins of a villa in Pompeii. Unlike most ancient statues, this one gave Brinkmann a head start, because copious evidence of original paint survived.

“There are rich traces of pigment which we analyzed using noninvasive methods such as UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy,” he explains. “What we do is absolutely faithful, based on physical and chemical measurements.”

Brinkmann is struck by the synergy of form and color in modeling the goddess’s act of disrobing. “The spectator,” he says, “awaits the next second, when her nakedness will be displayed. The sculptor creates a mantle that is heavy on the upper rim, to clearly explain that it will slide—and enhances this narrative by giving the rim its own color.”

German

archaeologist Vinzenz Brinkmann (Vinzenz Brinkmann) conducted a computer

reconstruction of the color of ancient Roman statue of Venus Lovatelli. This

sculpture I c. n. e. once adorned the house of a wealthy resident of Pompeii.

Unlike most ancient white marble statues on the sculpture of Venus preserved

flakes. This allowed the archaeologist with the method of optical spectroscopy

to investigate the chemical composition of the paint without damaging the surface

of the statue. Thus obtaining color reconstruction is absolutely plausible,

based on the results of the physical and chemical studies of the original paint

material. Now we can look at Venus Lovatelli eyes of its creator, and make sure

that the ancient masters were fans not only form, but also the colors.

The

Lovatelli Venus may be one of the earliest examples of private art collecting,

Brinkmann says. The work lent a decorative flourish to a nouveau-riche

household.Leave your preconceived notions of ancient art at home. This shows how marble statues actually looked in antiquity: covered from head to toe in vibrant paint. "The exhibition corrects a popular misconception,"

says Susanne Ebbinghaus, curator of ancient art at the Sackler, who points out that people generally associate classical art with white marble sculpture.

"What you would have seen when you walked through an ancient city, cemetery, or sanctuary," she explains, "would have been colorful sculpture: painted marble, colorful bronze, gold and ivory cult images. It completely changes our picture of the ancient world."

To the Greeks, the marriage of color and form had deeper connotations, suggests Harvard art historian Susanne Ebbinghaus. She points to a passage in Euripides, in which a remorseful Helen bewails her role in sparking a catastrophic war:

If only I could shed my beauty and assume an uglier aspect

The way you would wipe color off a statue.

The way you would wipe color off a statue.

“The

passage is very interesting,” Ebbinghaus says, “because it conveys the

superficial, transient nature of paint—it can be easily removed. But at the

same time, if we take the words literally, what the paint contains is the very

essence—the beauty—of an image.”

“Gods in Color: Painted Sculpture of Classical Antiquity” features full-size color reconstructions that challenge the popular notion of classical white marble sculpture, illustrating that ancient sculpture was far more colorful, complex, and exuberant than is often thought.

The reconstructions are the result of more than two decades of painstaking research by a pair of married German archaeologists, Vinzenz Brinkmann and Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann.

The Brinkmanns used various methods to detect the almost invisible traces of paint on the surfaces of the sculptures they studied.

Among these was the use of raking light to reveal incised details as well as subtle patterns caused by the uneven weathering of different paints on the stone surface;

ultraviolet (UV) light to bring out slight surface differences;

and techniques such as X-ray fluorescence and infrared spectroscopy to analyze the types of pigments employed.

Brinkmann microscopic analysis to reveal traces of paint not apparent to the naked eye,

as well as raised areas that paint protected from erosion.

Ancient texts and scientific analysis identify ancient paints: mostly a mix of mineral pigments with organic binders such as egg or wax.

Often only the lowest layers of paint survive. And some colors (red, blue) seem to last better than others. So the re-creations are a mix of evidence, guesswork, and approximation.

They then use 3D scanners to create plaster and synthetic marble reconstructions, which Brinkmann has painted by hand using the same kinds of mineral pigments classical painters would have mixed themselves.

It's hard to tell how accurately they reproduce the original colors. Often, upper layers of pigment eroded and left only the first layer. "It's standard to find red in the hair or iris," says Ebbinghaus. "But it's unlikely that so many Greeks had red hair, and even less likely that they had red eyes."

Brinkmann makes educated guesses, based on pigment analysis, literary references, and the coloring on ceramic relics, which have been better preserved than ancient sculptures.

The earlier the statue, the simpler the pigmentation, says Ebbinghaus. As time went on, classical artists began to mix pigments and add layers of color to skin and clothing.

In all, there are 20 reconstructions in "Gods in Color," each as dramatic and telling as the next. It's a good selection, ranging from the earlier, stiffer Archaic Era (600-480 BC) through the increasingly realistic and dramatic sculptures of the Classical (480-330) and Hellenistic (330-31 BC) eras in

Not surprisingly, the color research opens much of the work up to new interpretations.

The results are spectacular and reveal much about the way ancient Greeks and Romans viewed their world.

Center: Grave stele of Paramythion, color reconstruction (Photo courtesy Stiftung Archäologie, Munich)

Left and Right: Original sculpture in ultraviolet light (Photo courtesy Stiftung Archäologie, Munich)

Original (not on view in the exhibition); Greek, ca. 380-370 B.C.; marble, height 92 cm; Staatliche Antikensammlungen und Glyptothek, Munich

Grave stele of Paramythion, Greek, c. 380-370 B.C. from the Staatliche Antikensammlungen und Glyptothek, Munich. The stele appears as is (left), as it was, and as is under ultraviolet light.

The elegant vase is a container for the water of the bridal bath. On her tomb, it signals that the young woman Paramythion, shaking hands with her father or the groom, died before marriage.

Head of Caligula

Original (not on view in the exhibition): Roman, A.D. 39-41; marble, height 31 cm; Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen

Right:Original (Courtesy of the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen)

Left:Head of Caligula, color reconstruction (Photo courtesy Stiftung Archäologie, Munich)

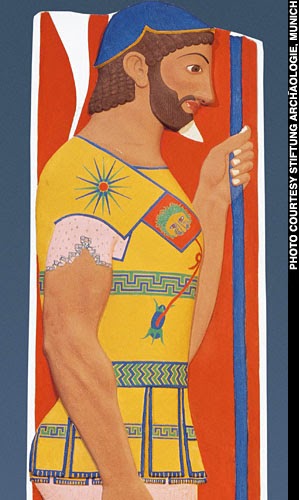

The painted replica of a c. 490 B.C. archer (at the Parthenon in Athens) testifies to German archaeologist Vinzenz Brinkmann’s painstaking research into the ancient sculpture’s colors.

The original statue came from the Temple of Aphaia on the Greek island of Aegina.

Trojan archer from the west pediment of the Temple of Aphaia on AeginaThe original statue came from the Temple of Aphaia on the Greek island of Aegina.

Original (not on view in the exhibition): Greek, ca. 490-480 B.C.; marble, overall height ca. 147 cm; Staatliche Antikensammlungen und Glyptothek, Munich

He is probably Paris, who killed Achilles with an arrow to that famous heel. He wears the costume of the Scythians of central Asia.

Left: Original sculpture

Right: Trojan archer from the west pediment of the Temple of Aphaia on Aegina, color reconstruction (Photo courtesy Stiftung Archäologie, Munich)

Right: Trojan archer from the west pediment of the Temple of Aphaia on Aegina, color reconstruction (Photo courtesy Stiftung Archäologie, Munich) Right: Original sculpture in ultraviolet light, detail of pant pattern (Photo courtesy Stiftung Archäologie, Munich)

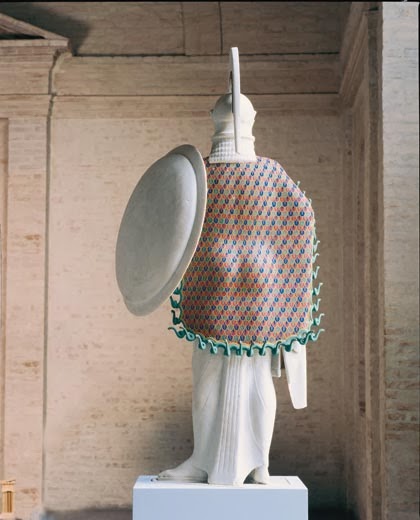

Left: Athena from the west pediment of the Temple of Aphaia on Aegina

Original (not on view in the exhibition): Greek, ca. 490-480 B.C.; marble, overall height ca. 340 cm; Staatliche Antikensammlungen und Glyptothek, Munich

Right: Athena from the west pediment of the Temple of Aphaia on Aegina (view from behind), color reconstruction (Photo courtesy Stiftung Archäologie, Munich)

Vinzenz Brinkmann typically leaves areas white where no evidence of original coloration is found. This rear view of the statue emphasizes the elaborate detailing of Athena’s aegis, or cape, trimmed with the life-like bodies of partially uncoiled green snakes.

In the middle of the battle between the Greeks and Trojans are goddess Athena calm during his auspices - the ormkantade mantle

Right: Original sculpture in ultraviolet light, detail of scales on the goatskin coat (aegis) (Photo courtesy Stiftung Archäologie, Munich)

Left: Lion from Loutraki, color reconstruction (Photo courtesy Stiftung Archäologie, Munich)

Its stunning blue-colored mane is not unique on ancient monuments. Lions often sat atop tombs in ancient Greece, where ornamental details such as the animals’ tuffs of hair and facial markings were painted in bright colors that accented their fur.

Original (not on view in the exhibition); Greek, ca. 550 B.C.; limestone, height 53 cm; Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen

Detail of mane and eyebrow hair visible with the naked eye on the original sculpture (Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen)

Archaeologists such as Germany’s Vinzenz Brinkmann are reconstructing some of the colorfully painted sculptures and glittering bronze statuary that existed during classical antiquity. A replica of a stele erected c. 510 B.C. on the grave of the Greek warrior, Aristion, commemorates his exploits in battle. He is dressed in yellow bronze or leather armor, a blue helmet (part of which is missing), and matching blue shinguards trimmed in yellow

Left: Aristion, detail of color reconstruction (Photo courtesy Stiftung Archäologie, Munich)

Right: Original sculpture in raking light, detail of a lion's head on the shoulder flap of the warrior's cuirass (Photo courtesy Stiftung Archäologie, Munich). Original (not on view in the exhibition); Greek, ca. 510 B.C.; marble, height 202 cm; National Archaeological Museum, Athens

|

| Alexander Sarcophagus |

Alexander Sarcophagus

A re-creation of the “Alexander” Sarcophagus, from about 320 BC, shows Greek warriors buck-naked save for some helmets, shields, and capes, while their Persian enemies sport brightly striped and patterned tunics, pants, and coats. The Persians’ elaborate garb suggests how the Greeks viewed them after they defeated them: a people made girly and weak by luxury. Here the reconstructed color helps make plain the prejudices of the Greeks and Romans, and in turn asks us to consider our own.

Restoration of polychrome said the sarcophagus of

Alexander, from the royal necropolis of Sidon, depicting the battle of Issus.

Study: Vinzenze Brinkmann and Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann. Stereolithography:

Alphaform, Munich. Restoration of missing parts: Joseph Kotti, Sylvia Kellner.

Painting: Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann. Original: National Archaeological Museum of

Istanbul. Exhibition "Bunte Götter" in the version shown in Athens.

Original (not on view in the exhibition): Greek, ca. 320 B.C.; marble, height of friezes 58 cm; Istanbul, Archaeological Museum

Above: Alexander Sarcophagus, color reconstruction of part of one long side (Photo courtesy Stiftung Archäologie, Munich)

The “Alexander Sarcophagus” (c. 320 B.C.), was found in the royal necropolis of the Phoenician city of Sidon.

But it was named for the illustrious Macedonian ruler, Alexander the Great, depicted in battle against the Persians in this painted replica.

Alexander’s sleeved tunic suggests his conquests have thrust him into the new role of Eastern King, but his lion-skin cap ties him to the mythical hero, Herakles, and alludes to divine descent.

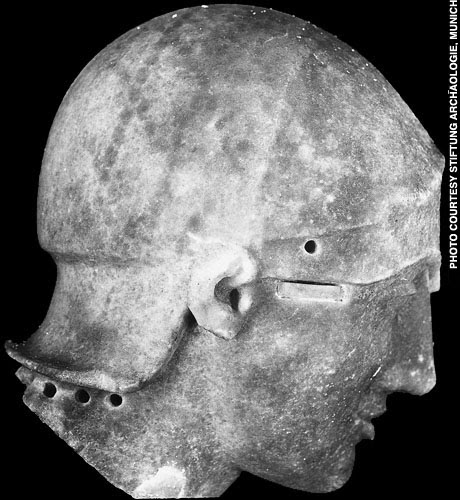

Warrior's head from the east pediment of the Temple of Aphaia on Aegin

Original (not on view in the exhibition); Greek, ca. 480 B.C.; marble, height 24 cm; Staatliche Antikensammlungen und Glyptothek, Munich

Left: Warrior's head from the east pediment of the Temple of Aphaia on Aegina, color reconstruction (Photo courtesy Stiftung Archäologie, Munich)

Original sculpture in ultraviolet light, showing scales on the helmet (Photo courtesy Stiftung Archäologie, Munich)

Original (not on view in the exhibition); Greek, ca. 480 B.C.; marble, height 24 cm; Staatliche Antikensammlungen und Glyptothek, Munich

"Peplos" Kore (translated as "maiden wearing a robe"). While traces of blue, green and red pigments on the statue indicated it had once been elaborately painted — the statue’s long hair was a vibrant chestnut — the Peplos Kore initially gained fame for its pale, almost otherworldly, marble sheen.

Even as the field of archaeology continued to develop and scholars learned more about the context in which it and the other statuary were originally created, it would still take more than a century to uncover the truth of the statue’s identity — a mystery solved by color.

Carved around 530 B.C.E. during the Archaic Period, the Peplos Kore belonged to the time of the Greater Panathenaia, the most important and grandest festival in honor of the city’s patron goddess, Athena.

After intense athletic and musical competitions, the best-looking citizens marched to the Acropolis to present Athena with a peplos, a rectangular garment that was wrapped around the body and fastened with pins at the shoulders. (Yes, they dressed a statue.)

Young women devoted to this cult had statues dedicated in their honor, so scholars assumed that the Peplos Kore represented the daughter of a wealthy Athenian wearing a peplos.

This statue, broken and buried in the dirt, speaks to the spirit of a civilization. The true colors of the Peplos Kore express just how vibrant the Greek experiment in democracy really was — a culture, much like any other, that made itself up as it went along.

"Peplos" kore, two color reconstructions (Photo courtesy Stiftung Archäologie, Munich)

The “Peplos” kore, Greek, c. 530 B.C., Acropolis Museum, Athens. The version at right was done first and drew criticism from those who say that the ancients painted only ornaments and details, never a whole sculpture.

The second version is limited to colors that can be determined surely. “If there is color preserved on the hair of statues of Greek women and some men,” notes curator Susanne Ebbinghaus, “it is red. The red must have served as a base color, and so the yellow kore has been given brown hair.”

Peploforosback

Peploforosfront

Left: Original sculpture in raking light, detail of garment hem (Photo courtesy Stiftung Archäologie, Munich)

Right:Original sculpture in ultraviolet light, detail of garment decoration above the belt (Photo courtesy Stiftung Archäologie, Munich)

Torso of a warrior, Greek, c. 470-460 B.C., Acropolis Museum, Athens. The color of the cuirass is speculative, and both yellow and gilt reconstructions were made; some ancient statues certainly were gilded.

A reconstruction in bronze of the head of a young athlete shows he has been crowned with the fillet of a victor.

Based on an original dating from the early 1st century A.D., the head was found in Naples in the 1700s as part of a complete figure.

Reportedly, its discoverers detached the head when they realized the metal statue was too heavy to carry away intact.

The striking effect of the portrait is accentuated by inlaid eyes made of silver, with pupils of red semi-precious stones, and gilding on the lips, brows and fillet.

It's grounding to see true antiquities beside Brinkmann's reconstructions, which have such comic-book pizzazz they seem almost unbelievable.

East Frieze detail representing the battle of Troy,

Achilles against Memnon. Reproduction of the Treasury of Siphnos - Delphi,

Archaeological Museum of Delphi

Restoration of polychrome

decoration of the frieze of the Treasury of Sifnos, in the sanctuary of Apollo

at Delphi in 525 BC. AD, representing the Trojan cycle. Study: Vinzenz

Brinkmann. Painting: Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann. Color copy: University of

Göttingen. Original: Archaeological Museum of Delphi. Exhibition "Bunte

Götter" in the version shown in Athens.

While many questions remain about painted classical sculptures, "Gods in Color" makes boldly clear that history is not what we have pictured. The ideal forms of physical beauty and realism have not changed.

They're just a lot more colorful than many of us ever imagined.

*original post Aug 5 2009

Sources:

smithsonianmag.com

archaeology.org

ueforum.se

Wikimedia Commons

online.wsj.com

athensnews.g

Wikipedia

Stiftung Archäologie, Munich

.jpg)

.bmp)

That does shed a new light on it, doesn't it?

ReplyDeleteThe scientific "re-colouring" to see how it would have looked is fascinating.

It sure did!

ReplyDeleteSo ingrained in our minds

the notion that for them

to be classic,

these admired Greek

and Roman sculptures

should be drab and monochromatic.

When unearthed in the 19th century

showing traces of original pigments

on these masterpieces,

the paint-job (though garish

on some),

caused a total paradigm shift:

now, people are able

to see the 'grandeur'

of the original coloring

and gilded accessories,

for what they truly were...

Indeed! Thanks for sharing. :^)

ReplyDeleteUnlike these guys, I now know the truth, having been enlightened. Interesting. It must have been a colorful world.

ReplyDelete--M

Absolutely!

ReplyDeleteIn ancient Rome and Greece,

life was about beauty

more so, in the arts-

that beauty depended on mimesis

(Greek word for realistic imitation).

Everything was tinted in living color

which was by all means, more realistic-

wipe color off a statue,

strip their paint and it's like

you stripped their good looks, too.

Imagine classical antiquity in

monochromes... dull and dingy.

It would be very hard to imagine

that they could have ever started

life as monochromes.

Lifelike sculptures were the pride

and joy of Greek and Roman art,

so why would artists then

could have missed out on

using paint to liven them up further?

Thanks for your comment, M.

Now you're one of us

who know the truth . lol

The truth of a bright-hued antiquity...