The origins of the divine

proportion

In the Elements, the most influential mathematics textbook ever written, Euclid of Alexandria (ca. 300 BC) defines a proportion derived from a division of a line into what he calls its "extreme and mean ratio."

A straight line is said to have been cut in extreme and mean ratio when, as the whole line is to the greater segment, so is the greater to the lesser.

In other words, in the diagram below, point C divides the line in such a way that the ratio of AC to CB is equal to the ratio of AB to AC. Some elementary algebra shows that in this case the ratio of AC to CB is equal to the irrational number 1.618 (precisely half the sum of 1 and the square root of 5).

C divides the line segment AB according to the Golden Ratio

Leonardo of Pisa was born around 1170 AD in (of course)

While traveling through

To be honest, the sequence sees little publicity these days outside of a Dan Brown novel and the occasionally nerdy conversation which may or may not involve warp core propulsion mechanics.

However, the Fibonacci sequence is an amazing bit of numbers that ties nature and mathematics together in surprising ways. From deep sea creatures to flowers to the make-up of your own body, Fibonacci is everywhere.

The Golden Ratio

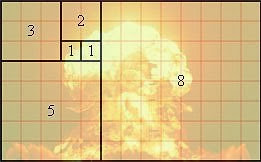

Most of the interesting things we find that relate to the Fibonacci sequence are actually more closely related to a number that is derived from Fibonacci, called the golden ratio.

If we take each number of the Fibonacci sequence and divide it by the previous number in the sequence (i.e. 2/1, 3/2, 5/3, 8/5), a pattern quickly emerges.

As the numbers increase, the quotient approaches the golden ratio, which is approximately 1.6180339887. Approximately.

Applications for the golden ratio have been found in architecture, economics, music, aesthetics, and, of course, nature.

In Architecture

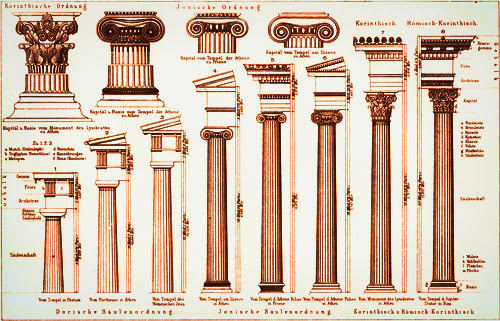

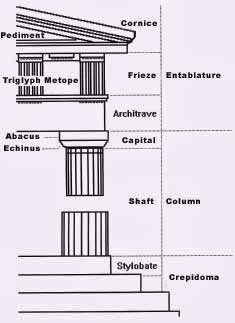

Three Greek columns; Ionic, Corinthian and Doric made up of the capital, shaft and base. Of the three columns found in

They have a capital (the top, or crown) made of a circle topped by a square. The shaft (the tall part of the column) is plain and has 20 sides.

There is no base in the Doric order. The Doric order is very plain, but powerful-looking in its design.

Doric, like most Greek styles, works well horizontally on buildings, that's why it was so good with the long rectangular buildings made by the Greeks.

The area above the column, called the frieze [pronounced "freeze"], had simple patterns. Above the columns are the metopes and triglyphs.

The metope [pronounced "met-o-pee"] is a plain, smooth stone section between triglyphs. Sometimes the metopes had statues of heroes or gods on them.

The triglyphs are a pattern of 3 vertical lines between the metopes.

The column is the most significant element because it defines the general proportions (module = ratio between the height and the width, defined by the semi-diameter of the shaft of the column in its lowest part). One recognizes the order by the shape of the capitals.

In the Doric order, the shaft of the column, which tapers towards the top and has between 16 and 20 flutings, stands without a base on the Stylobate, which is the uppermost step (of 3 or more steps) of a platform called Crepidoma.

The capital consists of the Echinus and the quadrangular Abacus and carries the architrave with its Frieze.

In Doric order the frieze is made up of metopes, plain, smooth stone sections (sometimes filled with sculpture) between the triglyphs carved with a pattern of three plane vertical arrises, survival of the wooden structure of primitive temples. The triangular pediment is ornamented with acroteriums.

The Ionic order has slenderer and gentler forms than the Doric male order. The crepidoma has more steps (8, 10 or 12) and the column now stands on a base.

The Ionic order has slenderer and gentler forms than the Doric male order. The crepidoma has more steps (8, 10 or 12) and the column now stands on a base. The flutings of the columns are separated by narrow ridges.

The Ionic capital, which is a Greek transformation of the Aeolic capital (

The architrave is made up of three superposed flat sections. The frieze is continuous, without triglyphs to divide it up. This order appeared for the first time in the 6C BC in the Greek centers of Ionia (western

The Corinthian order is similar to the Ionic except in the form of the capital.

Its characteristic feature is the acanthus leaves which enclose the circular slender body of the capital.

This order was much favored by the Romans who combined the volutes of the Ionic to the acanthus leaves of the Corinthian orders, creating the composite order.

Following excerpt from:

Secrets of the Parthenon

Salamis Stone

MARK WILSON JONES (

L- Doric engineering specification

And there are, in fact other feet. For example, this dimension here is one Ionic foot. So there is a, kind of, whole network of different interrelated measurements here.

NARRATOR: The Salamis Stone represents all the competing ancient Greek measurements: the Doric foot, the Ionic foot, and, for the first time, the Common foot—virtually the same measurement we use today.

Wilson Jones finds evidence of all three measuring systems in the height of the Parthenon.

MARK WILSON JONES: That distance is, at one and the same time, 45 Doric feet, that's the ruler on the relief; it's also 48 Common feet, which is the foot imprint; and it's 50 Ionic feet, all at the same time. And these are quite exact correspondences.

NARRATOR: So the Salamis Stone may have provided a simple way for ancient workers from different places to calibrate their rulers and cross-reference different units of measurement.

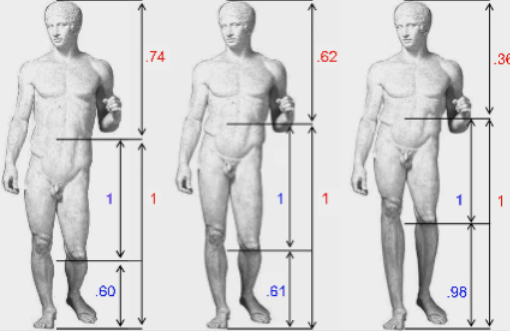

This stone, found on the island of Salamis and dated to the fourth century BC, gives standard measures for the orguia (from fingertip to fingertip with arms outstretched), cubit (from fingertip to elbow), foot, and span (from tip of thumb to tip of little finger, with hand outstretched). The cubit here is 487 mm, the foot 301 mm, and the span 242 mm; the orguia is unknown because the stone is broken, but it would be approximately 6 feet or 1800 mm. The stone is on display at the Peiraios Museum.

But the Salamis Stone may also be a clue to how the ancient Greeks were using the human body to create what we now regard as ideal proportions.

MARK WILSON JONES: What's extraordinary about this, is that at the same time as being a practical device, it's also a kind of model of theory, architectural theory, that a perfect, ideal human body, designed by nature, is a kind of paradigm for how architects should design temples.

NARRATOR: Among the first to record that Greek temples were based on the ideal human body was the Roman architect, Marcus Vitruvius.

He studied the proportions of temples like the Parthenon, in the first century B.C.E., 400 years after it was built.

MANOLIS KORRES: Vitruvius's work gives us the overall frame which is necessary to understand the system of proportions of the Parthenon.

NARRATOR: According to Vitruvius, Greek architects believed in an objective basis of beauty that mirrors the proportions of an ideal human body.

They observed, among many examples, that the span from finger tip to finger tip is a fixed ratio to total height, and height is a fixed ratio to the distance between the navel and the foot.

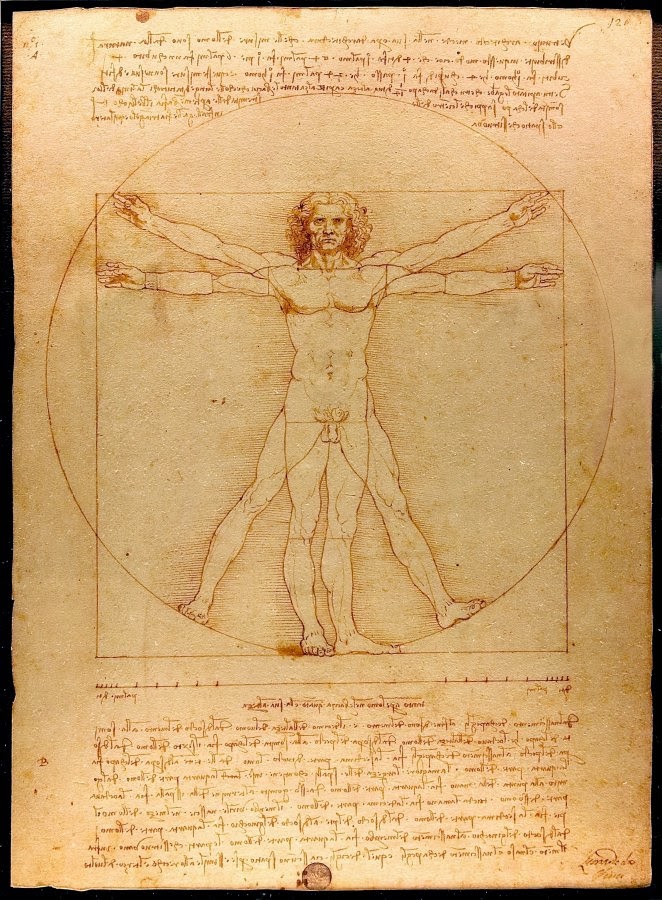

Two thousand years after the Parthenon, another artist was also searching for an objective basis of beauty.

And what's really interesting for us is that when we superimpose the

There are differences, but it's the same principle. You have the same interest in the anthropomorphic principle of getting a kind of sacred fundamental justification for these measures.

NARRATOR: Da Vinci's ideal Renaissance man famously stands in a circle surrounded by a square.

Da Vinci named this image "Vitruvian Man" after the Roman architect.

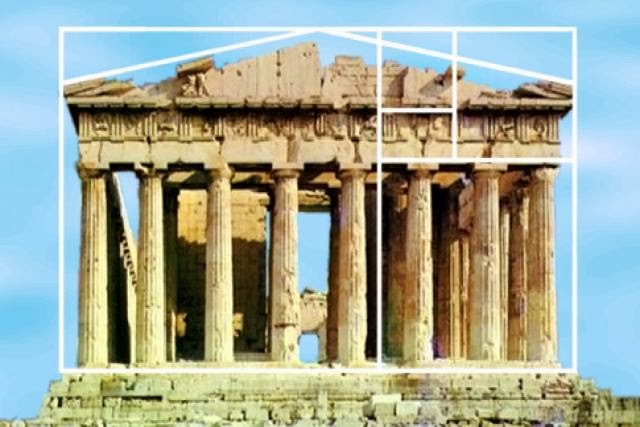

The ratio of the radius of the circle to a side of the square is 1 to 1.6. That ratio is sometimes attributed to the Greek mathematician, Pythagoras, who lived 100 years before the building of the Parthenon. In the Victorian age, it became known as the "golden ratio."

The ratio of the radius of the circle to a side of the square is 1 to 1.6. That ratio is sometimes attributed to the Greek mathematician, Pythagoras, who lived 100 years before the building of the Parthenon. In the Victorian age, it became known as the "golden ratio."

It was a mathematical formula for beauty. For centuries many scholars believed the golden ratio gave the Parthenon its tremendous power and perfect proportions. Most notably, the ratio of height to width on its facades is a golden ratio.

Today the golden ratio's use in the Parthenon has been largely discredited, but Manolis Korres and most scholars believe another ratio does in fact appear in much of the building.

MANOLIS KORRES: The width, for instance is 30 meters and 80 centimeters; the length is 69 meters and 51 centimeters, the ratio being 4:9.

NARRATOR: The 4:9 ratio is also found between the width of the columns and the distance between their centers, and the height of the facade to its width.

JEFFREY M. HURWIT: The Parthenon, like a statue, exemplifies a certain symmetria, a certain harmony of part to part and of part to the whole.

There's no question that the harmony of the building, which is clearly one of its most visible characteristics is dependent upon a certain mathematical system of proportions.

MARK WILSON JONES: For the Greeks, there was nothing better than a design based on the coming together of measures, of proportions and harmonies and shapes.

It's rather like an orchestrated piece of music in which the harmonies of the various instruments are, sort of, fused together in a wonderful, glorious, orchestrated symphony.

NARRATOR: With something like the Salamis Stone's use of the human body as units of measure, and the idealized human form to define perfect proportions, the Parthenon literally embodies the words of the Greek philosopher Protagoras, who lived in

"Man is the measure of all things".

In the Arts

Many books claim that if you draw a rectangle around the face of Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa, the ratio of the height to width of that rectangle is equal to the Golden Ratio.

No documentation exists to indicate that Leonardo consciously used the Golden Ratio in the Mona Lisa's composition, nor to where precisely the rectangle should be drawn.

Nevertheless, one has to acknowledge the fact that Leonardo was a close personal friend of Luca Pacioli, who published a three-volume treatise on the Golden Ratio in 1509 (entitled Divina Proportione).

.jpg)