The origins of the divine

proportion

In the Elements, the most influential mathematics textbook ever written, Euclid of Alexandria (ca. 300 BC) defines a proportion derived from a division of a line into what he calls its "extreme and mean ratio."

A straight line is said to have been cut in extreme and mean ratio when, as the whole line is to the greater segment, so is the greater to the lesser.

In other words, in the diagram below, point C divides the line in such a way that the ratio of AC to CB is equal to the ratio of AB to AC. Some elementary algebra shows that in this case the ratio of AC to CB is equal to the irrational number 1.618 (precisely half the sum of 1 and the square root of 5).

C divides the line segment AB according to the Golden Ratio

Leonardo of Pisa was born around 1170 AD in (of course)

While traveling through

To be honest, the sequence sees little publicity these days outside of a Dan Brown novel and the occasionally nerdy conversation which may or may not involve warp core propulsion mechanics.

However, the Fibonacci sequence is an amazing bit of numbers that ties nature and mathematics together in surprising ways. From deep sea creatures to flowers to the make-up of your own body, Fibonacci is everywhere.

The Golden Ratio

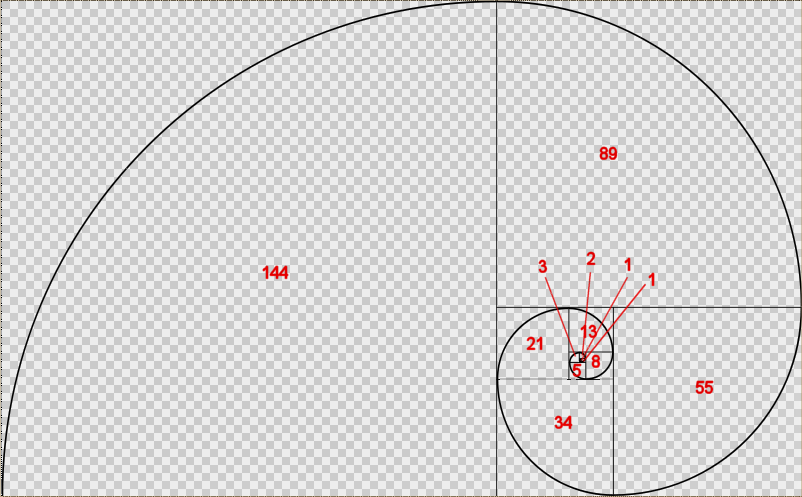

Most of the interesting things we find that relate to the Fibonacci sequence are actually more closely related to a number that is derived from Fibonacci, called the golden ratio.

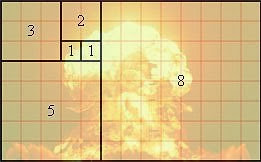

If we take each number of the Fibonacci sequence and divide it by the previous number in the sequence (i.e. 2/1, 3/2, 5/3, 8/5), a pattern quickly emerges.

As the numbers increase, the quotient approaches the golden ratio, which is approximately 1.6180339887. Approximately.

Applications for the golden ratio have been found in architecture, economics, music, aesthetics, and, of course, nature.

In Architecture

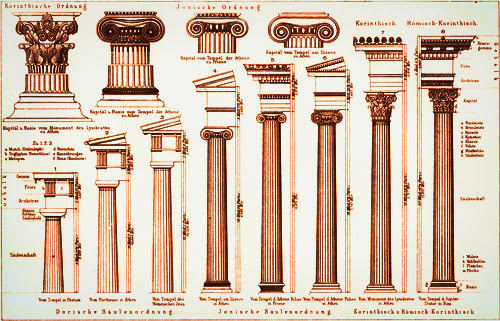

Three Greek columns; Ionic, Corinthian and Doric made up of the capital, shaft and base. Of the three columns found in

They have a capital (the top, or crown) made of a circle topped by a square. The shaft (the tall part of the column) is plain and has 20 sides.

There is no base in the Doric order. The Doric order is very plain, but powerful-looking in its design.

Doric, like most Greek styles, works well horizontally on buildings, that's why it was so good with the long rectangular buildings made by the Greeks.

The area above the column, called the frieze [pronounced "freeze"], had simple patterns. Above the columns are the metopes and triglyphs.

The metope [pronounced "met-o-pee"] is a plain, smooth stone section between triglyphs. Sometimes the metopes had statues of heroes or gods on them.

The triglyphs are a pattern of 3 vertical lines between the metopes.

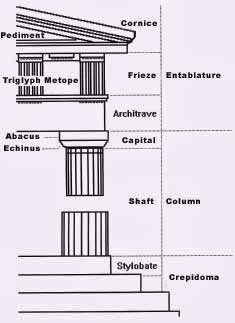

The column is the most significant element because it defines the general proportions (module = ratio between the height and the width, defined by the semi-diameter of the shaft of the column in its lowest part). One recognizes the order by the shape of the capitals.

In the Doric order, the shaft of the column, which tapers towards the top and has between 16 and 20 flutings, stands without a base on the Stylobate, which is the uppermost step (of 3 or more steps) of a platform called Crepidoma.

The capital consists of the Echinus and the quadrangular Abacus and carries the architrave with its Frieze.

In Doric order the frieze is made up of metopes, plain, smooth stone sections (sometimes filled with sculpture) between the triglyphs carved with a pattern of three plane vertical arrises, survival of the wooden structure of primitive temples. The triangular pediment is ornamented with acroteriums.

The Ionic order has slenderer and gentler forms than the Doric male order. The crepidoma has more steps (8, 10 or 12) and the column now stands on a base.

The Ionic order has slenderer and gentler forms than the Doric male order. The crepidoma has more steps (8, 10 or 12) and the column now stands on a base. The flutings of the columns are separated by narrow ridges.

The Ionic capital, which is a Greek transformation of the Aeolic capital (

The architrave is made up of three superposed flat sections. The frieze is continuous, without triglyphs to divide it up. This order appeared for the first time in the 6C BC in the Greek centers of Ionia (western

The Corinthian order is similar to the Ionic except in the form of the capital.

Its characteristic feature is the acanthus leaves which enclose the circular slender body of the capital.

This order was much favored by the Romans who combined the volutes of the Ionic to the acanthus leaves of the Corinthian orders, creating the composite order.

Following excerpt from:

Secrets of the Parthenon

Salamis Stone

MARK WILSON JONES (

L- Doric engineering specification

And there are, in fact other feet. For example, this dimension here is one Ionic foot. So there is a, kind of, whole network of different interrelated measurements here.

NARRATOR: The Salamis Stone represents all the competing ancient Greek measurements: the Doric foot, the Ionic foot, and, for the first time, the Common foot—virtually the same measurement we use today.

Wilson Jones finds evidence of all three measuring systems in the height of the Parthenon.

MARK WILSON JONES: That distance is, at one and the same time, 45 Doric feet, that's the ruler on the relief; it's also 48 Common feet, which is the foot imprint; and it's 50 Ionic feet, all at the same time. And these are quite exact correspondences.

NARRATOR: So the Salamis Stone may have provided a simple way for ancient workers from different places to calibrate their rulers and cross-reference different units of measurement.

This stone, found on the island of Salamis and dated to the fourth century BC, gives standard measures for the orguia (from fingertip to fingertip with arms outstretched), cubit (from fingertip to elbow), foot, and span (from tip of thumb to tip of little finger, with hand outstretched). The cubit here is 487 mm, the foot 301 mm, and the span 242 mm; the orguia is unknown because the stone is broken, but it would be approximately 6 feet or 1800 mm. The stone is on display at the Peiraios Museum.

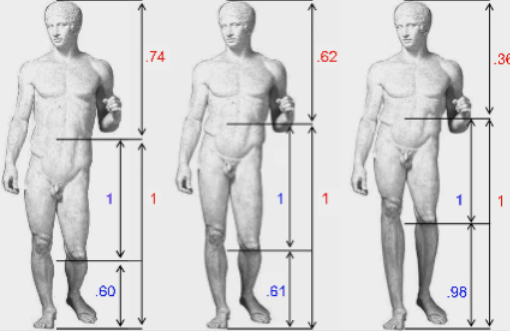

But the Salamis Stone may also be a clue to how the ancient Greeks were using the human body to create what we now regard as ideal proportions.

MARK WILSON JONES: What's extraordinary about this, is that at the same time as being a practical device, it's also a kind of model of theory, architectural theory, that a perfect, ideal human body, designed by nature, is a kind of paradigm for how architects should design temples.

NARRATOR: Among the first to record that Greek temples were based on the ideal human body was the Roman architect, Marcus Vitruvius.

He studied the proportions of temples like the Parthenon, in the first century B.C.E., 400 years after it was built.

MANOLIS KORRES: Vitruvius's work gives us the overall frame which is necessary to understand the system of proportions of the Parthenon.

NARRATOR: According to Vitruvius, Greek architects believed in an objective basis of beauty that mirrors the proportions of an ideal human body.

They observed, among many examples, that the span from finger tip to finger tip is a fixed ratio to total height, and height is a fixed ratio to the distance between the navel and the foot.

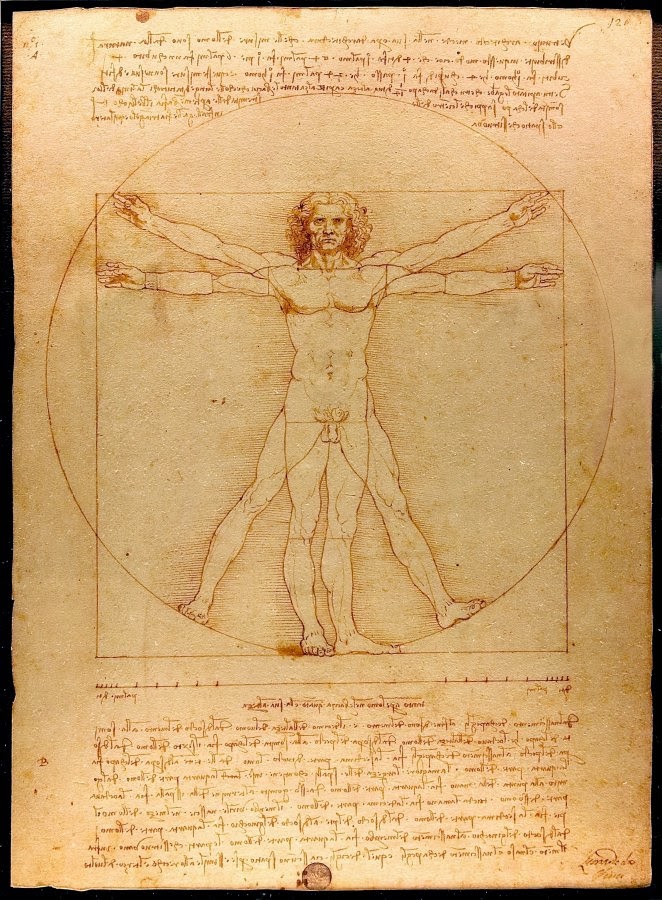

Two thousand years after the Parthenon, another artist was also searching for an objective basis of beauty.

And what's really interesting for us is that when we superimpose the

There are differences, but it's the same principle. You have the same interest in the anthropomorphic principle of getting a kind of sacred fundamental justification for these measures.

NARRATOR: Da Vinci's ideal Renaissance man famously stands in a circle surrounded by a square.

Da Vinci named this image "Vitruvian Man" after the Roman architect.

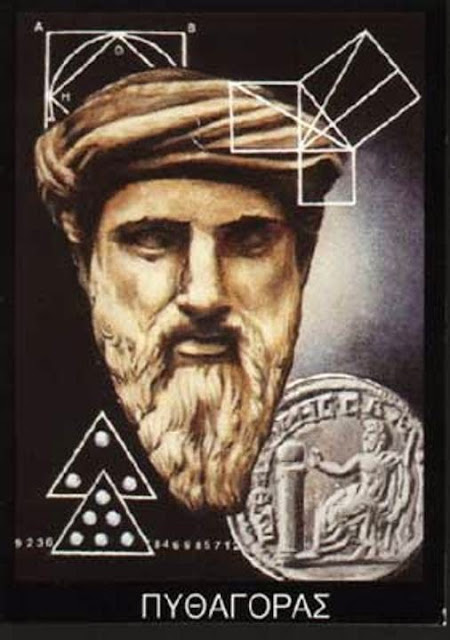

The ratio of the radius of the circle to a side of the square is 1 to 1.6. That ratio is sometimes attributed to the Greek mathematician, Pythagoras, who lived 100 years before the building of the Parthenon. In the Victorian age, it became known as the "golden ratio."

The ratio of the radius of the circle to a side of the square is 1 to 1.6. That ratio is sometimes attributed to the Greek mathematician, Pythagoras, who lived 100 years before the building of the Parthenon. In the Victorian age, it became known as the "golden ratio."

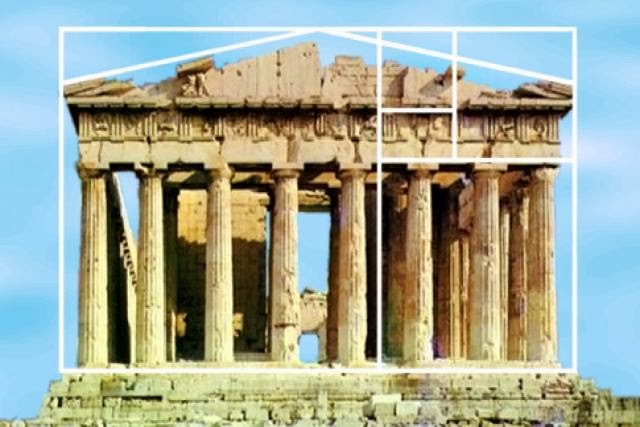

It was a mathematical formula for beauty. For centuries many scholars believed the golden ratio gave the Parthenon its tremendous power and perfect proportions. Most notably, the ratio of height to width on its facades is a golden ratio.

Today the golden ratio's use in the Parthenon has been largely discredited, but Manolis Korres and most scholars believe another ratio does in fact appear in much of the building.

MANOLIS KORRES: The width, for instance is 30 meters and 80 centimeters; the length is 69 meters and 51 centimeters, the ratio being 4:9.

NARRATOR: The 4:9 ratio is also found between the width of the columns and the distance between their centers, and the height of the facade to its width.

JEFFREY M. HURWIT: The Parthenon, like a statue, exemplifies a certain symmetria, a certain harmony of part to part and of part to the whole.

There's no question that the harmony of the building, which is clearly one of its most visible characteristics is dependent upon a certain mathematical system of proportions.

MARK WILSON JONES: For the Greeks, there was nothing better than a design based on the coming together of measures, of proportions and harmonies and shapes.

It's rather like an orchestrated piece of music in which the harmonies of the various instruments are, sort of, fused together in a wonderful, glorious, orchestrated symphony.

NARRATOR: With something like the Salamis Stone's use of the human body as units of measure, and the idealized human form to define perfect proportions, the Parthenon literally embodies the words of the Greek philosopher Protagoras, who lived in

"Man is the measure of all things".

In the Arts

Many books claim that if you draw a rectangle around the face of Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa, the ratio of the height to width of that rectangle is equal to the Golden Ratio.

No documentation exists to indicate that Leonardo consciously used the Golden Ratio in the Mona Lisa's composition, nor to where precisely the rectangle should be drawn.

Nevertheless, one has to acknowledge the fact that Leonardo was a close personal friend of Luca Pacioli, who published a three-volume treatise on the Golden Ratio in 1509 (entitled Divina Proportione).

Another painter, about whom there is very little doubt that he actually did deliberately include the Golden Ratio in his art, is the surrealist Salvador Dali.

The ratio of the dimensions of Dali's painting Sacrament of the Last Supper is equal to the Golden Ratio.

Dali also incorporated in the painting a huge dodecahedron (a twelve-faced Platonic solid in which each side is a pentagon) engulfing the supper table.

The dodecahedron, which according to Plato is the solid "which the god used for embroidering the constellations on the whole heaven," is intimately related to the Golden Ratio - both the surface area and the volume of a dodecahedron of unit edge length are simple functions of the Golden Ratio.

He positioned the two disciples at Christ's side at the golden sections of the width of the composition. In addition, the windows in the background are formed by a large dodecahedron.

Dodecahedrons consist of 12 pentagons, which exhibit phi relationships in their proportions.

These two examples are only the tip of the iceberg in terms of the appearances of the Golden Ratio in the arts.

The famous Swiss-French architect and painter

Le Corbusier, for example, designed an entire proportional system called the "Modulor," that was based on the Golden Ratio.

The Modulor

But why would all of these artists (there are many more than mentioned above) even consider incorporating the Golden Ratio in their works?

The attempts to answer this question have led to a long series of psychological experiments, designed to investigate a potential relationship between the human perception of "beauty" and mathematics.

Is beauty in the eye of the beholder?

- Is your mouth's width 1.618 times the width of your nose?

- Is your entire length 1.618 times the distance from the floor to your belly button?

- Are your eye teeth 1.618 times the width of the teeth next to them?

- Are the bones in your fingers, starting with the tips, 1.618 times the length of each other?

In particular, British psychologist Chris McManus in 1980, acknowledged that "whether the Golden Section [another name for the Golden Ratio] per se is important, as opposed to similar ratios (e.g. 1.5, 1.6 or even 1.75), is very unclear."

The entire topic received a new twist with a flurry of psychological attempts to determine the origin of facial attractiveness.

For example, psychologist Judith Langlois of the

He asserted that the reason we classify certain people as beautiful is because they come closer to Golden Ratio proportions in the face than the rest of the population.

Many disagree with both Langlois's and Lowey's conclusions. Psychologist David Perret of the

Furthermore, when computers were used to exaggerate the shape differences away from the average, those too were preferred.

Perret claimed to have found that his beautiful faces did have something in common: higher cheek bones, a thinner jaw, and larger eyes relative to the size of the face.

An even larger departure from the "averageness" hypothesis was found in a study by Alfred Linney from the Maxillo Facial Unit at

Using lasers to make precise measurements of the faces of top models, Linney and his colleagues found that the facial features of the models were just as varied as those in the rest of the population.

L- Dr. Mario Livio

If you have the patience to juggle and manipulate the numbers in various ways, you are bound to come up with some ratios that are equal to the Golden Ratio.

In spite of the Golden Ratio's truly amazing mathematical properties, and its propensity to pop up where least expected in natural phenomena, I believe that we should abandon its application as some sort of universal standard for "beauty," either in the human face or in the arts.”- Dr. Mario Livio

In Nature

At first glance, this series might look like the idle musings of a bored person before Tivo was invented, but it goes much further than that. Pause whatever live broadcast you’re watching and take a look at the following examples.

Efforts have been made to improve the illustration with special effects.

The Nautilus is a cephalopod that inhabits the ocean at a depth of about 300 meters and is officially the ugliest animal we have ever seen.

If we take the above spiral and rotate it around the the central axis, we get an almost perfect approximation of a spiral galaxy.

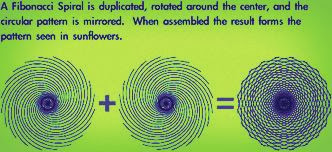

The sunflower naturally evolved a method to pack as many seeds on its flower as space could allow.

Additionally, the number of lines in the spirals on a Sunflower is almost always a number of the Fibonacci sequence.

Like the sunflower, the pine cone evolved the best way to stuff as many seeds as possible around its core.

Also, in what was surely an accident, it evolved into perhaps the best substitute for toilet paper when in a pinch.

The golden ratio is the key yet again. As with the sunflower, the number of spirals almost always is a Fibonacci number.

Human body

The golden ratio is found throughout your body, all the way to your DNA.

Here’s one you can see for yourself, dear reader, if you’re still with us.

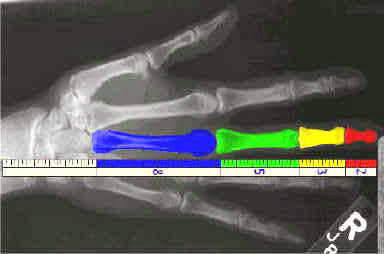

If you use your fingernail length as a unit of measure, the bone in the tip of your finger should be about 2 fingernails, followed by the mid portion at 3 fingernails, followed by the base at about 5 fingernails.

Humans exhibit Fibonacci characteristics, too. The Golden Ratio is seen in the proportions in the sections of a finger. (It is also worthwhile to mention that we have 8 fingers in total, 5 digits on each hand, 3 bones in each finger, 2 bones in 1 thumb, and 1 thumb on each hand. Coincidence? You decide.)

The final bone goes all the way to about the middle of your palm, which is a length of about 8 fingernails.

Again, it’s Fibonacci at work and the ratio of each bone to the next comes very close to the golden ratio.

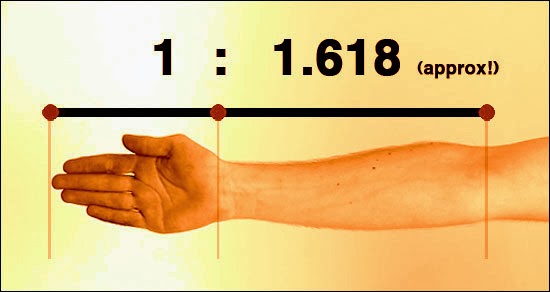

Continuing with the length of your hand to your arm is, again, the golden ratio.

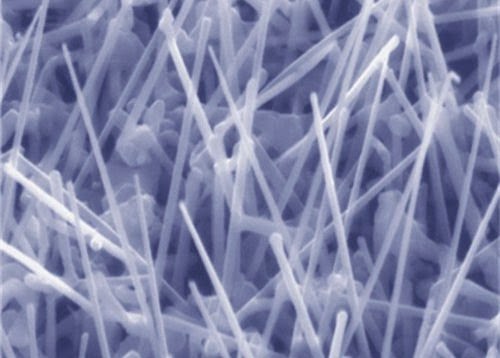

Fibonacci applies even down to what makes you, you. A DNA strand is exactly 34 by 21 angstroms.

The Fibonacci sequence is truly a wonder. The examples are vast, and go way beyond the scale of this article.

The patterns in which a tree grows branches,

the way water falls in spiderwebs,

even the way your own capillaries are formed can all be linked to Fibonacci.

Science is just beginning to understand the implications of this simple sequence and some of the most amazing discoveries may be yet to come.

*original post 6/14/09

* Brad Handley *

* Mario Livio *

*threes.com*

*PBS.org*

.jpg)

.jpg)

Excelent post, thank you

ReplyDeleteit's absolutely wonderful.. I read 'The Ancient secret of the flower of life' from Drunvalo Melchizedek about this topic.. A passionate subject.. Thank you !

ReplyDeleteYou're welcome...

ReplyDeleteHi, Boruel :-)

Thank you, Jeff... :-)

ReplyDeleteNo matter how math-phobic

anyone is, it's always

enlightening to understand

that there exist this fabulous

realm and order in most of life

and nature sequences -

the Golden Ratio, 1.618, that is,

rings true to almost everything,

like, how could anyone fathom

that there's a remarkable sequence

to the spiraling two-dimensional

order of the distribution of seeds

in a sunflower going round

and round the sides,

both clockwise and counterclockwise

directions from the center

until they interlace?

Melchizedek must be a good read :-)

Yes my beautiful friend another interesting concept discovered or rediscovered?We must chat on the subject soon xoxo

ReplyDeleteDiscovered and in existence

ReplyDeletesince the Ancient Greeks,

particularly Pythagoras and Phidias (formula for phi)

observed certain patterns

and number relationships

occurring in nature.

Friend, you might be

interested to know, too,

that Fibonacci numbers

are also found in an

ocean wave pounding the shore... ;-)

The universe as well as our nature tends to repeat,have you heard of the I think it's called the mandibol set.It's a pattern or formula that repeats it's self constantly forever.Plus it's fascinating & pretty to look at as a picture.I like the idea of fractiles also when I first heard of them.I was thinking of some of the older civilisations Mayans like the Maya,I think there are a couple more also,that knew of pi & used amazing numbers we only now use computers for.Not to mention the amazingly accurate calendar they made,that we make use of.The Egyptians for there pyramids.It's fantastic how they all managed to make such accurate monoliths & cities.I tend to think we might have other civilisations also as you need math to create.

ReplyDeleteOr mandilbolt something like that it was quite sometime ago

ReplyDeleteWonderful sense of perspective,

ReplyDeleteI agree with your assessment

and intended point with regards to

the Egyptians and the Mayan civilization.

It started in Ancient Greece,

then to Central Africa (with the Ishango Bone)

and South America (the Incas and Mayans),

and then moves on to Egypt, Babylonia, China, India, ...

Reality is, the ancient Egyptians did possess

higher math and they purposely encoded

it into their construction....

if we carry out a thorough survey of the

Great Pyramid, Cheops, of Giza, Egypt,

the design of which is based on phi,

we are particularly struck by the

encoded high mathematics and its precision.

Pi is the ratio of a circle's diameter

to its circumference, 1:3.14 or 7:22.

Phi is the ratio of a line divided

so that the length of the shorter segment

bears the same relationship to

the length of the longer segment

as the longer segment bears to

the whole undivided line, 1:1.618.

This 'Phi' is sometimes called 'The Golden Section'

{attributed to Pythagoras}

because there's something

ineffably pleasing about the ratio--

It was used by many Renaissance artists

such as Poussin, Michelangelo and da Vinci;

it occurs in abstract mathematics,

as in this Fibonacci Series of

numerical progression;

it occurs frequently in nature,

for example in the successive length

of segments of the chambered nautilus,

etc, etc, etc

Overall, the golden ratio (or Phi),

is an excellent ratio for

packing together structures in nature

We use mathematics to describe anything

and everything in the known universe

and everything and anything in the unknown universe.

Math is 'proof' of man's glory in

a millions of years of evolution.

Spiral out ;-)

I admit to be clueless about this.

ReplyDeleteWhat's it about?

Here is one for you cheeky, it is also in the spiralling part of a wave too lol!

ReplyDeleteOoooh, yes, S :-)

ReplyDeleteWe find it in the

lovely, wide, deep,

willful sea waves....

It's a numeric sequence,that repeats it's self endlessly.They have made some computer generation of it.It's very beautiful to look at a gives the mind food for thought.I read about it a long time ago in a scientific magazine.

ReplyDeletemmmmmmmm waves lol.my beautiful C mmmmmmmmmmmmm also, kisses my sweetness.Come chat to me some time I miss you!

ReplyDeleteSteve meant Mandelbrot set...

ReplyDeleteMaybe more at the link...

http://mth151.wordpress.com/2009/02/19/mathematics-and-art-an-unlikely-connection/

And you wrote all about Fibonacci numbers without discussing reproducing rabbits which is the way people usually explain them... 1 pair of baby rabbits grow up and have 1 pair of babies, who then become adults and have babies themselves also...

b=baby pair, A = adult pair

b -> A -> Ab -> AAb -> AAAbb -> AAAAAbbb ->

count the number or rabbit pairs, the number of letters ... it goes 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, .... the Fibonacci numbers!!